I chose Holy Name Cathedral as the first church I would attend for a couple of reasons. For one, it is close by. And across the street from my gym, which means I walk by it four to five times a week. And second, it is the seat of the Catholic Archdiocese here in Chicago. So that seemed as good a place to start as any.

As for a little bit of history, this Roman Catholic congregation was established in 1852. Right before the church was formed, in 1846, Chicago had a population of around 14,000 people. An influx of German and Irish immigrants, most of whom were Catholic, were settling in large numbers north of the Chicago River. The only Catholic church around was St. Josephs, which was built by the Germans. As a result, mass was in Latin, but the sermons and confessions were in German.

Of course, the Irish didn’t understand the German, so Father Kinsella, himself Irish and the President of St. Mary of the Lake University, realized the city needed another parish for Irish immigrants. That parish was initially part of the university, and they used temporary meeting places for the first few years. But by 1851, Chicago’s population had grown dramatically to 35,000, and the congregation had grown so much that the bishop approved a permanent location. That building was completed in 1854 and served all English-speaking Catholics north of the river. Soon, Holy Name required four priests to run the church: Fathers Jeremiah A Kinsella, John Breen, William Clowry, and Lawrence Hoey.

However, it was difficult to retain bishops in Chicago. The population continued to explode, and the weather was rough. Bishop Anthony O’Regan reluctantly accepted the assignment in 1854 when the population of Chicago had grown to 66,000.

But his tenure was routinely troubled. His health was compromised, he was stressed about the completion of the Holy Name building, and he faced ugly accusations. As a result, he continually submitted his resignation, only for it to be repeatedly turned down.

One of the larger controversies during O’Regan’s assignment was the charge that he discriminated against the French congregations under his purview. One of his greatest critics was Rev. Charles Chiniquy from a parish in Kankakee on the South Side. In retaliation, O’Regan threatened to excommunicate him.

Chiniquy wrote about his experience with what appears to be a corrupt O’Regan in his 1886 book Fifty Years in the Church of Rome.

From Chicago to Cairo [Illinois], it would have been difficult to go to a single town, without having, from the most respectable people, or reading in big letters, in some of the most influential papers, that Bishop O’Regan was a thief or a simoniac, or a perjurer, or even something worse. The bitterest complaints were crossing each other over the breadth and length of Illinois, from almost every congregation: “He has stolen the beautiful and costly vestments we bought for our church,” cried the French Canadians of Chicago. “He has swindled us out of a fine lot given us to build our church, sold it for $40,000, and pocketed the money, for his own private use, without giving us any notice,” said the Germans.

Chiniquy went to Chicago to see for himself and to confront the bishop.

I found that it was too true that the bishop had stolen the fine church vestments, which my countrymen had bought for their own priest, for a grand festival; and he had transferred them to the cathedral for his own personal use. … The second thing I did was to go to the cemetery, and see for myself, to what extent it was true or not that our bishop was selling the very bones of his diocesans, in order to make money. [He was.]

When Chiniquy confronted the bishop, O’Regan said, “All those things are mine. I do what I please with them. You must be mute and silent when I take them away from you.”

O’Regan then took Chiniquy to court, accusing him “falsely of crimes.” Chiniquy won the case, but the bishop appealed and had the venue moved to Urbana. And remarkably, a young Abraham Lincoln agreed to defend Chiniquy against the tyranny of the bishop. And he won the appeal.

The bishop followed up by threatening to excommunicate Chiniquy, and he then removed the French-speaking priests from Chicago.

He basically did the same thing at Holy Name Cathedral. Right before O’Regan finally left Chicago in 1857, he got rid of the church’s four founding priests. O’Regan claimed it was due to financial problems, but the priests were very unhappy with his running of the church and made their complaints known. The congregation was also unhappy and came to the support of the banished priests. They held an emergency meeting where they declared confidence in the priests and agreed to forward their complaints to Rome.

I really wanted to spend some time on the history of this very early Chicago church because one thing I find is that there are often reports of founders and/or preachers in some of these newer non-denominational churches commiting a wide assortment of financial and sexual crimes. And of course, there was the recent priest sex scandal in the Catholic Church. It got me thinking about whether our society has just degenerated to the point where our religious leaders have fallen. But no, these types of corruption have been part of church leadership since the beginning. After all, the leaders are only human and easily corrupted by power, whether today or a hundred and fifty years ago. I should also point out that such corruption is not limited to churches and organized religion. It should go without saying, but I often hear people forget about this fact. All you have to do is look at what happens in Chicago (or anywhere in the United States/world) politics, schools, media, etc. to know this is true.

Or just read what follows!

Moving on with the story of Holy Name Cathedral…

In 1871, the infamous Chicago fire tore through the city. And Holy Name fell victim; the church was completely destroyed. The replacement building was completed one block away in 1874-5 and is the one still in use today.

The next infamous chapter in the cathedral’s history is its connection with Chicago’s bootlegging wars and mob violence during the 1920s. Across the street from the cathedral was Schofield’s Flower Shop, which while a working florist was also a front for the North Side Gang, primarily an Irish mob. The leader of the gang, Dion O’Banion was a part owner and also ran the shop, “where murders, boot-legging, and hi-jackings were planned amidst flowering plants and the scent of roses.” [Chicago Daily Tribune, August 14, 1960]. But O’Banion also sang in the choir at Holy Name Cathedral when he was a child.

The North Side Gang was the main rival of The Outfit, an Italian mob led by the notorious Al Capone and Johnny Torrio. In 1921, the two groups came to an agreement to cooperate. But the deal fell apart, and the result was a hit put out on O’Banion.

On November 10, 1924, O’Banion was in the flower shop preparing flowers for the funeral of gangster Mike Merlo, who had died of cancer. When Al Capone’s men, Frankie Yale from Brooklyn and two others from Chicago, arrived at the shop to ostensibly pick up the flowers for the funeral, they instead executed O’Banion, shooting him multiple times at close range, right across from Holy Name.

Needless to say, this triggered a rivalry that turned very bloody. Polish-American Hymie Weiss, took over leadership of the North Side Gang after O’Banion’s killing. It was said that he was the only man that At Capone feared. And he was bent on revenge.

In January 1925, the North Side Gang shot up Al Capone’s car, but Capone survived. Later that same month, Weiss and two others ambushed Torrio and shot him, leaving him for dead. But he survived and fled to New York.

In August 1926, Capone’s men attacked Weiss and others in a gunfight on Michigan Avenue a block or two south of the Chicago River. Everyone survived. But that led to a well-known attack on Capone as retaliation.

On September 20, 1926, ten cars shot over 1,000 rounds into Capone's Hawthorne Hotel in Cicero. It is believed that Weiss was present. But Capone was able to flee out the back of the building and escape. Obviously, there would be a price to pay for this brazen attack.

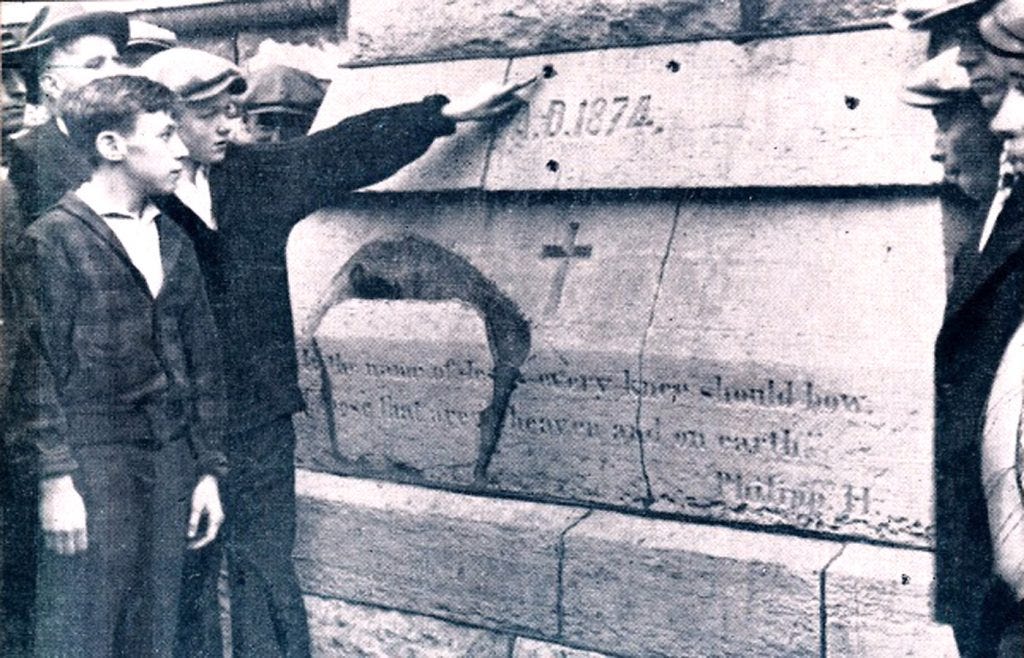

On October 11, 1926, Weiss, gangster Paddy Murray, and three others were returning to their offices at Schofield's Flowers from the Cook County courthouse where a partner of theirs was on trial for murder. They parked next to Holy Name Cathedral and as they walked in front of the church to cross the street to the shop, bullets hailed from the second floor of a rooming house next door to the flower shop. Weiss and Murray were both hit and dropped dead.

In Weiss’s pocket was a list of the names of all the men on the jury of his partner’s trial. I think we can guess the purpose of that list.

And Holy Name Cathedral was pocked with bullet holes. An inscription on a cornerstone was so badly damaged that the passage inscribed on it no longer made sense. An article in a 1929 edition of the Chicago Tribune states, “'Every knee should heaven and on earth.' The English translation of the Vulgate's version of the words which St. Paul wrote to the Philippians is, 'At the name of Jesus, every knee should bow in heaven and on earth.' Literally, you see, gangdom shot piety to pieces in Chicago."

The section of the building was eventually removed. And other holes were filled in. A few are barely visible today.

One other interesting connection to this event. I live in an apartment building that used to be a hotel owned by Alex Louis Greenberg. He and his wife, as well as other mobsters, also lived here. Greenberg was reportedly the financial advisor (racketeer?) for Al Capone and others in the mob.. In fact, he was business partners in the Malt-Maid Brewery with none other than Dion O’Bannion and Hymie Weiss.

But in 1955, Greenberg was fatally shot on the way to their car as he and his wife left the Glass Dome Hickory Pit at 2724 S. Union Ave on the South Side of Chicago. He wife was unharmed, but when questioned, she insisted it was a robbery.

A couple of gangsters, Sam Tassone and Walter Monahan, were called in for questioning, but were released, and no one was ever arrested for the murder. Part of the problem was that no one could figure out why he was hit. At the same time, three other pretty big hits also took place, so one thought was younger guys cleaning up by getting rid of the older guys. Another theory was a fear that Greenberg might turn government witness, but there wasn’t any reliable evidence of that.

One final piece of history is that in 1979, Pope John Paul II became the first Pontiff to visit Holy Name Cathedral.

I first noticed this church on the way to my gym, which is across the street in the exact spot where Schofield's Flower Shop once stood. And there was a group of people standing outside protesting. After my yoga class, I wandered over to find out what they could possibly be protesting. This is when I learned that Holy Name was the seat of the Chicago Archdiocese. And as such, the group was protesting new restrictions on performing Latin Mass. Apparently Chicago was taking the new Vatican policy even more seriously than required. There is a church here in Chicago that does conduct a Latin Mass, so that is on my list of places to visit. I’ll expand on that whole controversy once I have attended.

It probably goes without saying that the cathedral is gorgeous. And huge. It was the first mass of the year, and the place was packed. I couldn’t help but wonder if a lot of people attending were tourists. So many people had their phones out and were taking photos and selfies. It also appeared that no one knew each other. At least there were no visible greetings occurring anywhere around me.

I felt somewhat disconnected from the service. It is the first time I’ve been to a church service in years. Who knows how many years! But the choir and pipe organ up in a loft in the back, provided hauntingly beautiful music.

The mass was as expected. Nothing really stood out. But oddly, as soon as the priest introduced the Lord’s Prayer, I perked up. And I found myself reciting it along with everyone else. I can only suppose that was because it is the only part of the service that I am familiar with, that I feel comfortable with. We said the same Lord’s Prayer throughout my childhood:

Our Father, who art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy Name.

Thy Kingdom come.

Thy will be done

On earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive them that trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

The power, and the glory,

For ever and ever.

Amen.

I held my breath after “forgive our…” Is it going to be trespasses (the correct word!) or debts? A quick Google search told me that Presbyterian or Reformed traditions typically say “debts.” And Anglican/Episcopal, Methodist, or Roman Catholic traditions are more likely to say “trespasses.” So there you go.

But then came the most dreaded part of the service! Peace be with you.

The priest said, “The custom of exchanging the greeting of peace at Mass is found in the words of St Augustine in the 4th century: After the Lord's Prayer, say 'Peace be with you.' Christians then embrace one another with a holy kiss. This is the sign of peace.”

It’s funny, because as I know it’s coming, I start planning. Do I turn around? Do I go to the person to my right? To my left? No one is in front of me for a couple of rows, so I don’t have to worry about that. I also hate when everyone around me turns away from me, and then I’m left hanging. It’s so awkward.

As it turned out, the woman to my right and I turned to each other first. She was probably five feet from me. Just as I started to move toward her, she lifted her hand and waved to me. I waved back. Then I looked around. Everyone was waving to each other. Waving to people sitting next to them and waving to people on the other side of the church. The last time I had been to a church, people hugged at this point. This was so weird. A crowd of people in a room waving to each other. And sad.

Next came communion. The priest actually put on a mask. He hadn’t worn one all service, and only a few in the congregation wore one. Nobody else up on the altar wore one either, even those helping to serve communion. That bothered me. The priest was a young man, so he wasn’t at risk. And if any elderly people or people at risk were going to be taking communion or were concerned, they could be and probably were wearing their own mask.

It was hard not to feel like the priest needed to protect himself when coming face-to-face with the unwashed masses - us. So much of the church is set up to separate the priest with the congregants. This was just another example.

I certainly did not take communion. I am not a Catholic. But one woman with her husband and two children were in line to receive the eucharist. And the mom was videoing her kids while walking toward the altar. She continued to video as the priest gave her kids a blessing. Then she turned off the camera and put it away so she could take her communion. Hmmm. As I said earlier, tourists?

Another part of every church service - the offering. When the church asked for the offering, baskets were passed up and down the pews. But also, which I shouldn’t be surprised about, a QR code on the bulletin was available for donations too. What else was in the bulletin? Ads. Like those found in a yearbook or a Little League program. Ads for Chop House, the creation of wills, a nail salon, dating sites, a comedy writing class, a funeral home, a plumber, and even a pub. I understand the church needs to make money, but there is something very unbecoming and lacking reverence about accepting ads for the program.

For me and this project, the sermon will probably be the most important part of the service. Before I go into the subject of the sermon, I decided to look up whether that is even the correct word in the Catholic church because I had also heard the word homily in reference to a priest’s message. Here is what I found.

Apparently, prior to Vatican II in 1962 when Pope John XXIII created the council, the message was referred to as a sermon. Since then, it is usually called a homily. But the terms are not interchangeable.

In the past, the sermon was longer and more moralistic, a discussion of how to live a virtuous life. But the Vatican was not happy that the sermon typically did not address the “mysteries of faith” and as a result did not provide the doctrinal foundation by which a virtuous life is established. Vatican II sought to rectify this with the adoption of a homily.

Homilies are more informal and conversational. And guidance from Vatican II requires more biblical readings. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the homily follows the reading of Scriptures and is a scripturally-based reflection, “the aim being to explain the literal, and evolve the spiritual, meaning of the Sacred Text."

This particular service, it was announced, was dedicated to Mary. So the homily was about how Mary should be a model for us in the coming year. After all, Mary could have let the darkness of her situation blind her from the light. Instead, she demonstrates there is significance to all events in our lives, whether those events are big (a pandemic) or small (missing a green light on the way to church). Mary did not say no in times of adversity, such as when she learned she was with child. And as a result she, and all of us, received joy (through Jesus). In conclusion, he said, we should turn to Mary to be our guide and companion. We should leave our baggage of last year at the altar during eucharist and remember that each of us is “willed, necessary, and loved.”

It was a nice message, I suppose, but it certainly didn’t land as very profound or moving or enlightening.

The priest, Fr. Andy Matijevic, was very young, in his late twenties. Perhaps it was due to lack of experience, but he read his homily and was completely unemotional and disconnected. He sounded like a middle schooler reading from a textbook out loud in class: forced sing-songy, robotic. But perhaps he just needs more experience to come across as more natural.

At the end of the service, when I retreated towards the exit in the back, I noticed that the pews in the back of the church were filled with homeless people. One was a man with a plastic bag full of cans and bottles. Another had four plastic bags strewn across her pew, where she was the only one sitting. She was reading a very old, worn Bible.

And here are some final thoughts on my morning at Holy Name Cathedral. One issue is that I clearly have negative opinions about the Catholic Church that are difficult to ignore. For one, as a nonCatholic, I feel unwelcome. But I am pretty sure that is just in my imagination and based on my personal history.

I realize that friends of mine who are Catholics love the church because of the ritual and tradition. The service is the same wherever you go to a Catholic church. I can see how there is comfort in that. But as a guest/visitor, it feels very unwelcoming, like you aren’t part of the club. So it’s hard for me to feel the presence of God, whatever that might mean. But perhaps that is one of those things that you know when you feel it. And for some reason, because I feel like that even before going in, I have a defensiveness right away.

Because I taught for a handful of years at a Catholic middle school, Chaminade College Prep, I am definitely familiar with the service, the responses, and the movements. But I find myself defensively refusing to participate in them. It feels cultish for me, and it feels like I am just going along with the crowd, much like, and this is a weird comparison, a place like WaterWorld at Universal Studios when the employees are warming up the audience before the show. The audience just follows directions without thinking. “This side cheer!” “That side cheer!” Like trained seals. I can’t stand it.

I am really curious to see if I feel the same way in churches of other denominations and/or if my resistance to the Catholic mass reduces over time. Maybe with this experience, my walls will come down.

*** Next week: Fourth Presbyterian Church on Michigan Ave